Finding the needed support and getting proper counselling on mental health issues in Nigeria is often hampered by a lack of awareness, stigmatisation, and offensive comments borne out of ignorance. LARA ADEJORO speaks with a 26-year-old Nigerian filmmaker, Adebisi Peters, who is helping to change the narrative on the lack of knowledge and awareness of mental health conditions. He spoke on how his documentaries on depression is helping to improve mental health education.

For almost three years, Adebisi Peters wakes up daily questioning his existence. He felt unfulfilled and was only living for survival. He kept thinking of the life he wanted to live but was unable to achieve.

Despite working with well-known individuals and an international organisation, he felt empty. He knew something about him wasn’t working and he didn’t know how to go about it.

He said he would take up any job as a filmmaker just to fend for himself, his mother, and his younger brother, but noted that unknown to his family members and friends, he was falling apart.

He slipped into depression, became a shadow of himself, and couldn’t find help from the people he taught could help him come out of the crumbling mental health crisis.

“Any time I wake up in the morning or go for a production shoot, I question my existence and that puts me in a sad mood. I felt I was not living for the purpose I was created for. As I’m setting up production for others.

“I just feel sad because the kinds of productions I’ve always wanted to do are those that can help to tackle social vices, help societal transformation, educate people, and promote positivity.

“I was getting money but I did not have enough money for my production. So, I just had to continue to hustle and cater to myself, my mother, and brother but it was more like I’m useless,” he told our correspondent.

His depressing days became intense between 2020 and early 2021 during the peak of COVID-19 in Nigeria.

Recalling, he said “The job wasn’t coming because of COVID-19 and I couldn’t take care of my mother and brother. I was dormant, I didn’t have any social work I was doing. I’d always been surviving before this time but it became much more difficult and I felt useless even to my brother and mother because I couldn’t cater to them.

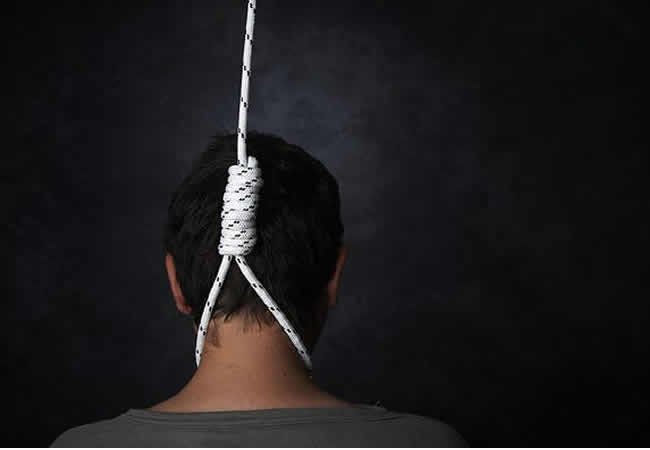

“It was around that time people were committing suicide and at that point, the social media responses to suicide were bad. So, I started thinking that people will condemn you for living and still condemn you for killing yourself. They will condemn you without knowing what the person went through. You will be blamed for living your life and you will be blamed for taking your life.”

‘Most people don’t even understand the context of the word depression’

The social filmmaker narrated that when he finally dared to confide in a few people, his quest for counselling, understanding, and help was greeted with laughter, jest, and mockery.

According to the World Health Organisation, depression is a common illness worldwide, with an estimated 3.8 per cent of the population affected, including 5.0 per cent among adults and 5.7 per cent among adults older than 60 years.

The WHO noted that approximately 280 million people in the world have depression.

“Depression is different from usual mood fluctuations and short-lived emotional responses to challenges in everyday life. Especially when recurrent and with moderate or severe intensity, depression may become a serious health condition. It can cause the affected person to suffer greatly and function poorly at work, at school, and in the family.

“At its worst, depression can lead to suicide. Over 700,000 people die due to suicide every year. Suicide is the fourth leading cause of death in 15-29-year-olds,” WHO said.

The 26-year-old man said no one understood his battles and the people he opened up to laughed at him and invalidated his feelings.

“I realised that most people don’t even understand the context of the word depression. Most people think you should not be depressed if you’re doing well, they think depression is about being poor or being sad.

“Most times, they make fun of it and when I talk to a few persons to help me through what I was going through and what they think I need to do to come out of it, they will just laugh it off and thought I didn’t know what I was saying.

“Meanwhile, what I told them was just the tip of the iceberg, I was feeling more depressed than I could express to them but they thought I was joking. So, I decided to keep it to myself,” he said.

Nigeria’s poor mental health policy

According to Statista – one of the world’s leading data platforms, Nigeria has a population of 216.7 million. Yet, the nation does not have comprehensive mental health laws and policies.

Experts have continued to advocate that the Mental Health Bill which ha d passed its first and second reading, as well as the public hearing stage, should be signed into law.

The bill when signed into law, they say, will help to promote the mental health and well-being of all Nigerians, as well as help achieve a stable mental health status for the country.

According to the information on the website of the Association of Psychiatrists in Nigeria, there are only 250 psychiatrists and 200 psychiatry trainees in the country; most of whom are based in urban areas.

In an article published in the Lancet Journal and titled ‘The Time is now: reforming Nigeria’s outdated mental health laws’, the authors noted that approximately 80 per cent of individuals with serious mental health needs in Nigeria cannot access care.

The authors said, “A paucity of community-based and primary health-care services means that access to care is restricted to the most severe cases, usually in the form of psychiatric inpatient care or makeshift institutions.

“The result is a chronically and dangerously under-resourced mental health system catering to the needs of an estimated one in eight Nigerian people who suffer from mental illness, poor awareness of the causes of mental health, widespread stigma and discrimination, poorly equipped services, and abuse of people with mental health problems.

“A reform of the mental health law that is in keeping with international standards is urgently needed to drive change.”

Copyright PUNCH.

All rights reserved. This material, and other digital content on this website, may not be reproduced, published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or in part without prior express written permission from PUNCH.

Contact: [email protected]