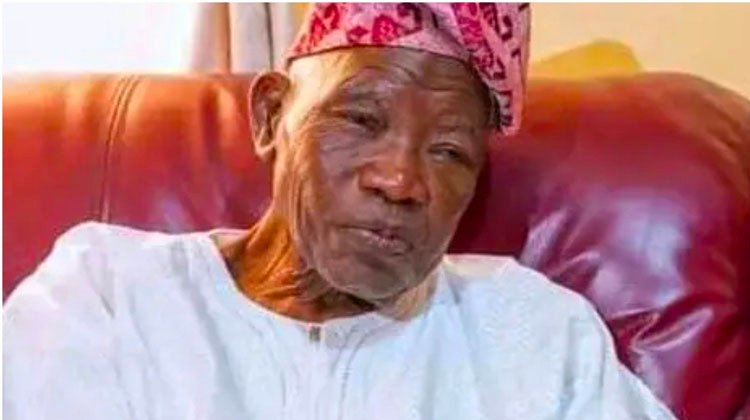

Alhaji Lateef Kayode Jakande would have turned 93 years on July 23, 2022 but even in death and almost four decades after leaving office, one can hardly forget this quintessential politician; a man of character and integrity. Jakande was a Nigerian journalist who became governor of Lagos State in Nigeria from 1979 to 1983. He died on February 11, 2021, at the age of 91. He set a legacy and pace with his unique style of leadership, a fine administrator whose name would continue to be remembered for generations unborn.

He governed Lagos state for a very short period of four years and 3 months before the military intervention led by current President, Major General Muhammadu Buhari. In spite of the short period, LKJ would be remembered for heading an administration that spearheaded monumental development strides in Lagos State and in Nigeria as Minister for Works. His administration has been credited with the growth, and transformation of Lagos to a modern city, with the birth of infrastructures in all sectors of the state. He introduced housing and educational programmes targeting the poor, building new neighbourhood primary and secondary schools and providing free primary and secondary education. LKJ stood out during the Second Republic which was an era where poor governance and embezzlement of public funds were the order of the day in Nigeria. He epitomised honesty, fairness, and justice.

The former Lagos State Governor was an astute believer in the doctrine of “The greatest good for the greatest number.’’ The concept of “the greatest good for the greatest number” is an axiom that hardly holds sway in reality. In a theoretical sense, there are rational clues that point to the advantage of having the majority benefits from a particular cause or series of causes. This is particularly true if we endeavour to dig deep into moral laws, or try to expand on those altruistic admonitions put forth by moralists. Beyond the scope of moral fabric, we all have been made to understand that a typical social design, albeit in variegated form—be it in economics, politics, business, religion or in our distinct cultures, was crafted for the benefits of society—or for the greatest number. But more often than not, we come to the realisation that these social processes hardly see the light of the day. The idea of “the greatest good for the greatest number” seemingly does not resonate purely with most human beings.

Human beings are more about themselves—their personal interests and, to some extent, like in politics—their kith and kin. It follows that altruism is but a far-reaching virtue that only a few men can express. Perhaps, the English philosopher, Jeremy Bentham, had thought about this virtue in the scope of a community or having people in large numbers when he philosophised on his utilitarian principle—one that emphasises keenly on “the greatest good for the greatest number”. Bentham thought that happiness and pleasure could be more universal than restrictive to a few sets of people. That people should only act in ways that promote social good and happiness—a kind of value similar to those upheld by the Epicureans of the ancient world. Strongly influenced by Bentham’s principle, John Stuart Mill thought that utilitarianism could be channelled in the best way possible through government. A liberal parliamentarian and philosopher in nineteenth-century England, Mill, was of the opinion that happiness enhances justice in a system, and public good and progress are at best achieved in a nation or a polity if the government sets its mind to undertake projects and programmes that would be beneficial to every social class in the society—be it the elites or the plebeians.

The utilitarian principle puts African politics in the spotlight for the wrong reasons, given that politics in the continent is hardly practised to uphold happiness for the greatest number. But when we look at the policies embarked on by Jakande when he was Lagos State Governor in the Second Republic, there is every reason to state that his approach to governance was philosophically utilitarian than everything else. The LKJ administration can be described as one that believes actions are right if they are useful or for the benefit of a majority. Jakande was an enigma, and he proved his mettle even beyond a reasonable doubt, approaching governance from a rather unique perspective, laying down markers that are still arguably hardly matched by subsequent administration in the state and Nigeria as a country.

In contemporary Nigerian political discourse, Jakande’s legacies resonated more with the programmes he had set up for educational excellence in Lagos. Being a highly cerebral man who understood how transformational education could be to the common man, the former governor provided free primary and secondary education, and built more schools to accommodate pupils and students regardless of their tribe or religion. The sociological effects of his educational programmes in the state are still very much felt today. It must be pointed out that this very policy attracted many people to Lagos, some of whom were poor parents who brought in their wards from other parts of Nigeria to Lagos in order to benefit from the free educational programmes.

To state clearly, Mr Jakande did not only just embark on policies and programmes for the fun of it, but his understanding of the sociological needs of Lagosians at that time informed his direction. His forthrightness should be a lesson for contemporary African politicians—especially those in Nigeria. It is beyond assumption but the reality is that almost nine out of ten Nigerian politicians vie for political positions to enhance their personal interest over social progress. These sets of men and women get into power almost always with the aim to steal and further their luxurious lifestyle. Most of them hardly engage in social infrastructural programmes to benefit the society they swore to serve and protect. Many of them travel to foreign countries for their medical vacations, send their kids to the best of schools abroad, and conduct their most serious and epicurean engagements in foreign lands, leaving so much to be desired for Nigeria’s infrastructural development. It is worthy of note that Mr Jakande was never in the rank of such politicians. As pointed out, he was focused more on the people under his watch.

Mr Jakande, having explored the characteristics of the Lagos society, knew so well that those that needed attention the most were the poor masses. As most Nigerian politicians have been known to conduct themselves, the former Lagos State chieftain was not elitist in nature. He did not join forces with other privileged individuals in the state to control power and resources, and impoverish the masses. The elite framework is by nature, a derivative characteristic in African politics. It has often been the case in Africa that men with low standing in society, after miraculously having a taste of power, suddenly embark on an ostentatious lifestyle and habits of material acquisitiveness. It is of note to state that Jakande’s mindset to power was beyond such petty indulgences. He took up the governmental mettle by laying concerted blueprints in improving the lives of impoverished Nigerians.

The question before us today is where are the likes of Lateef Jakande as Nigerians yearn for societal transformation? Why do transformational leaders continue to elude us in Nigeria? Why do we leave behind the likes of Jakande and continue to elect criminals, thieves who end up as treasury looters? Why do Nigerians detest and reject transformational leaders that could practise the doctrine of utilitarianism? Having seen what LKJ did in four years, the Nigeria electorate should by now know that politicians that offer money either naira or dollars in exchange for their votes cannot guarantee “the greatest good for the greatest number’’ but will only guarantee the greatest good for their pockets. It’s high time we shunned momentary benefits from corrupt politicians and started looking for those who will govern like Lateef Jakande, the servant of the people who in four years did what could only be described as a miracle of governance. May the soul of LKJ continue to rest in peace.

Akinfesoye writes via [email protected]