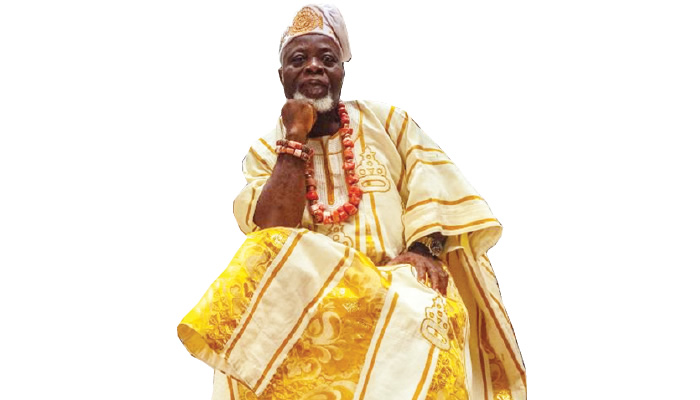

Visiting professor, University of California, Los Angeles, musician and renowned Batik tapestry and floatography artist, Prince Tunde Odunlade, shares with FATTEH HAMID his journey towards becoming a renowned artist

You’re currently 68, how has life been?

Age to me is a matter of number; I really don’t go by age because it’s not something I really talk about. I’ve seen people older than me that have no roof over their heads and I’ve seen those who are not as old as I am and have gone far in life. This is to thank God for all He has done and I pray that I live long to fulfil the destiny of God in my life.

You’ve had a lot of experiences, what will you say makes you fulfilled as a person?

The fact that I’m able to do the work that God has endowed, that God has embedded in me, the gift God has given me; in as much as I continue to do it in an atmosphere and environment that is conducive to allow my thoughts to flow freely, I recall every moment as the best I could do at that point and look for a better future too.

What was the education you received while you were developing?

Again, it’s another thing that I don’t talk so much about because my innate ability has been the fulcrum of my creative life. That is the natural gift that was given to me, especially when I was eight days old, coming from a royal family. In Il-Ife, there’s what they call Jala Moso which represents the male and female part of that clan. There, I was given some oriki (panegyric) that now became the vanguard of what I do today. The oriki vividly captures my life as a person, as an artist, and fundamentally as an individual who sees life as a gift and therefore shares that life with other people.

However, I went through primary and secondary education like every other person, and after my secondary education, I worked briefly as a salesperson. After that, the urge in me kept telling me that I had a call, and asking me when I was I going to respond to it. I saw an advert in a newspaper asking that people could come and be trained in graphics art which led me to come to Ibadan. However, I found out that the company was not quite sure of what it was doing. There was this camouflage; you know, being deceived when they were actually doing something else. Those kinds of things didn’t just start at this age; it has been on for a while. It was after that I found a job as a sales representative in an automobile company selling vehicles.

Did you settle in?

All along, I was not fulfilled because my mind continually told me that there was something in me that I ought to do. As fate would have it, I travelled to Ife and found out that my aunt, who was now living in the US, Aunty Florence Oluwayemisi, was married to Prince Adeyemi Oluwayemisi. He (Prince Oluwayemisi) is a great artist; his pen name is Yinka Adeyemi. I found out that my aunt has been married to him. So, I told my aunt, ‘I like what you’re doing. This is the reason why I went to Ibadan’. Then she said, ‘oh yeah, you like what we are doing?’ I said, ‘yes, I do.’ Then she gave me a piece of paper and I drew something. She was excited and took it to her husband upstairs.

Then they said, ‘‘Well, you can learn to do your art here if you like to’’, and I said ‘music is actually my interest, and my aunt told me that you (my aunt’s husband) are connected; you know Sunny Ade, and if you can introduce me to him, I will be more than glad because I like music.’ Then he said, ‘oh, well, introducing you to Sunny Ade is no big deal, but I can see your hand in this visual art, and you are good at it. Why don’t you get started with that? Then down the line, you will meet Sunny Ade.’ He was a prophet by saying that. I spoke with him, and that was sometime in 1973. I have been practising as an artist since then; it is 50 years this year. This is 2023. From the very day that I started, everyone could see the potential in me of becoming an artist, and the work began to come a few months after.

Within that 1973, I’ve produced works that attracted sales, that attracted acquisition. However, at Iowa State University, I studied Anthropology, then at Stillman College, Tuscaloosa, I studied there, and I’ve attended several workshops at different universities around the world. Now that I even teach in some of these universities which I’ve done several courses, it has become my developmental educational line that has taken me far and wide. I’m referred to as a professor at UCLA. That is University of California, Los Angeles. That is my educational development; I told you that I don’t really talk about it. Primarily, the innate ability in me has been so much more.

How did you make your first sale as an artist?

I think this was, November 30, 1973. I followed my mentor to Lagos and when we got to Lagos, there was a brother; his colleague, his name is Adebisi Fabunmi, one of the Osogbo artists, that’s his work there (pointing to some pieces of art), he had the gallery at the Ikeja Airport Hotel called Fab Osogbo. So, when we got there that afternoon, he was not around but his brother who is late now, we call him Ade, was there. He signed Quay Odu on his works. Quay Odu was at the gallery, and then he asked my mentor, Prince Yinka Adeyemi, if he brought any work and he responded that he did. He brought out his works and those works were hung on the wall of the gallery. He then asked me if I brought any pieces, and I told him that I had some small pieces. They were the size of the cardboard; so, that would be like 22 by 30 inches, four of them, pastel drawings, you know.

Then he asked to see them. I opened them up because I was sceptical because without having met Uncle Fab, whom I’ve heard a lot about his being tough, and you don’t mess up around him. After seeing them, he said we should put them up. I said, ah, don’t put them up, let Uncle Fab come and if he says, put it up, then you can put it up. So he took all four pieces from me and hung them in the gallery. Lo and behold, Uncle Fab came a few moments after that, and then was going around the gallery and saw my mentor’s works and acknowledged them. Then he saw mine and asked whose works they were and then Ade pointed at me that I was the owner. Immediately he heard that, he started pulling the works from the wall and flung them at me. I picked the works and rolled them up. There was a swimming pool directly in front of Uncle Fab’s gallery with a fence made out of barbed wire around the pool. So I went and stuck that paperwork in between the barbed wire.

What happened later that day?

Later in the evening, I, Ade, my mentor and this white folk came towards Uncle Fab and asked if the gallery was closed for the day. He pleaded that he was travelling the following day and needed some artwork. Apparently, the man was a pilot; I think it was British Caledonian or one of those foreign airlines that were coming to Nigeria then. So we came back to the gallery and opened the gallery. He went around the whole gallery and said he couldn’t find what he was looking for. So, my mentor and Uncle Fab left, and Ade and I were left with the white guy to close the gallery. After that, I went and pick my work from the barbed wire, where I left it and stuck it under my armpit. As we were going, the white guy spotted what was rolled up under my armpit, and inquired about what they were. Ade answered that they were my artwork, and the white folk asked to see them.

Then we went back to the front of the gallery with the light in front and we didn’t have to open the gallery. He (white folk) asked why we didn’t show them to him earlier. Well, I was still shivering. I didn’t know what would happen. I was scared. Then the white guy said he liked them and would love to pick them. He later purchased them for N30; each for N10. That was in 1973. I was excited, I ran to my boss and his colleague, Uncle Fab. I said that the white guy bought my works. Uncle Fab told me to bring the money. So, I gave him the N30, and he told me I should pay N10 as commission. I told him that was why I brought the money to him. So, I gave him all the N30 and he gave me N10 out of it to go and find change. I went and changed the money, and when I came back, he pulled N7.50 from the N10 naira and gave me N22.50 back. That means he pulled out N7.50 for his commission as the owner of the gallery, which was 25 per cent of the total cost of my works purchased by the white man. I took the money and went to buy one gallon of dry gin and give to my mentor and he prayed for me. So, that was my first sale as an artist in 1973.

You once mentioned at an event that you did some of the artwork in front of the palace of Alaafin in Oyo State. Did that really happen?

Yes. It did happen.

So, what year was that, and how did it go?

I think that was 1975/76. I was not the one who took the contract. I was working. I think it was in 1976; Yes. That was after we returned to Ibadan. It was sometime in 1976 when I was working with his musical band. I was playing drum for Kongas in the musical band of Ademola Onibonkuta. So, he was the one the late Alaafin of Oyo, Oba Lamidi Adeyemi III, gave the contract to decorate the Afin (palace). I worked with him. So, that was my opportunity of helping to decorate the palace of Alaafin. That was way back in 1976.

Do you have any vivid remembrance of the Alaafin at the time and when he later passed on?

Well, we were in the palace for four weeks doing his work, and every evening, he would come to us, after we must have worked. He would inspect what we had done. After that, he would go in and would bring a bottle of Schnapps. He might have taken a little out of the Schnapps and would give us the rest. All of us would drink it, while he would sit down around us, telling us stories about the palace; how he came into the palace, and what he found when he came into the palace and how he had improved, using his head of servants, Kudefu, as the witness for every point he made. I saw a vibrant, cerebral, intelligent, loving, Alafin. And even in 2021, after we had opened this place, he came here, December 2021. I recall he passed on in March or May 2022. So, a few months before he passed, he came to this gallery. I reminded him of the time we spent with him at the palace in 1976 with Ademola Onibonokuta, he was excited. So, it was like I encountered him when he was first installed as Alaafin, and I encountered him when he was about to pass on. I saw a more mature institution from when he first became the Oba.

Aside from arts, you are also into music. How did that start?

Is music not art? As far as I’m concerned, they are family; visual, drama, poetry, music, name it. To me, they are the same family, same father, different mothers. I’ve always believed that if you can do one, you can do the other because all of these have similarity. In music, you have tones, in visual art, you have tones. In music, you have perspective, in visual art, you have perspective. In music, you have sound, in visual art, you have sound. This is because when you are looking at something that is speaking to you, it becomes interpersonal communication between you and that piece of art; be it sculpture, painting, textile, whatever it is. So, I play music and I’ve recorded five albums to my credit. I’ve participated in a lot of dramatic presentations on radio, television, stage, so much that I was part of the first national drama troupe that was formed in Nigeria, in 1976, which formed the group that performed the play, ‘Langbodo’. That was Nigeria drama entry for FESTAC.

You once mentioned that you got married here Ibadan; did you meet your wife in Ibadan as well?

Yes, I did. Each time I went to visit my friend, Kehide Balogun, who was living in a one-bedroom apartment, hanging out, arguing around with him, the children of the landlord of the house came to his room to watch television. I got to know them. I really loved those kids. All of them are grown-ups now, grandmothers, and grandfathers. I told you that I love people. You know, we accommodate each other. In the process of that, my wife now who was in teacher’s college in Abeokuta came home and found out about me, that who’s this chap that all my younger ones are rallying around him? A party was organised that evening to celebrate one of her sister’s newborn babies, and I helped to organise a party. I was the MC of the party as well. So, she came home, but as we met during the party that very night, we knew right away that I was going to marry her.

What would you say was the highest point of your career as an artist?

It is yet to come, but if you want me to measure so far, and you want me to measure one or two years, I can recall when I had the opportunity of taking a group to America. So, that makes me feel like I can extend to other people the opportunities that I have. I was commissioned to bring a group to the US. The first time was in 1985. But that fell through. But down the line in 1992, I had the opportunity to do it and I took a group of some of my colleagues of younger generation to the United States. That gladdens my heart. The group was now featured on CNN, which makes me the first Nigerian artist to be featured on CNN on January 3, 1993. That gladdens my heart.

Also, when I was commissioned by the Federal Republic of Nigeria to use art to show the calamitous repercussion of how our external debt has been hampering our progress as a country. Then, when I had my first one-man show in New York in 1987, when I had my first one-man show in Nigeria, at the Federal Government College, Sokoto, I think that was in 1978. You know, I’ve had several moments that I can recall and say, wow! Again, when my works of art were collected by the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, United States; there are 10 of my works in their collections. That was a happy moment. Again, when my work was installed in the Lagos State Government House in Marina; I don’t know if they’re still there. That was in 1975/76. I’ve had many moments. When I recorded my first album, I couldn’t believe I could do it, but I did it. That was in 1986, and I titled it ‘Bolanle’. Many moments of my life still make me believe that my best is yet to come.