When I was growing up in Lagos, Nigeria, our home proudly displayed magnificent Benin artworks acquired by my father during Nigeria’s hosting of the Festival of Arts and Culture in 1977. The intricate craftsmanship and cultural significance of these pieces were evident, and we cherished them dearly. However, not everyone who visited our home shared the same appreciation. On multiple occasions, visitors would fixate on the artwork, but their expressions quickly turned uneasy as they made comments about the pieces being “satanic” or “idolatry” and even suggested that they were holding my father back in life.

Despite my father’s attempts to explain the historical and cultural importance of the works, their destructive beliefs persisted. Ironically, those who my father bothered to tell that the artworks were acquired during FESTAC 77 became even more convinced of their malevolence. Regrettably, the festival, meant to celebrate Africa’s rich cultural heritage, had been labelled as an event with evil spiritual connotations by many. This attitude persists today, as some individuals believe that demons reside in artworks, particularly old ones. Nollywood, Nigeria’s vibrant film industry is notorious for how it mirrors this perception. Its movies often feature storylines that demonise cultural artifacts, perpetuating the notion that they are associated with evil or supernatural powers.

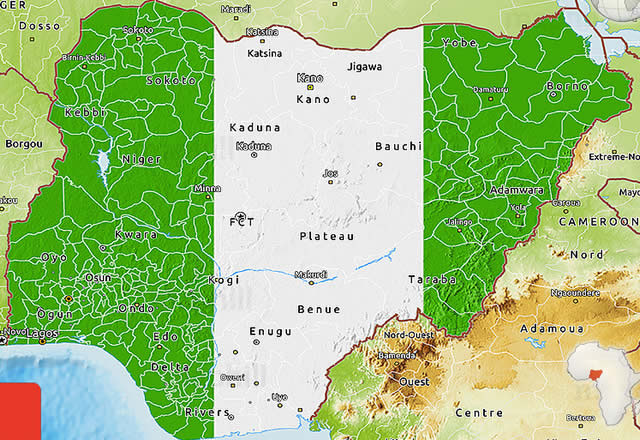

This state of affairs is a stark contrast to the global movement advocating return of looted treasures like the Benin Bronzes.The evidence on ground reveals a concerning reality inNigeria, where the majority of the population adheres to either Christianity or Islam with their adherents teaching and advocating strongly against the worship of other gods and idols, often equated with cultural artifacts in the form of sculptures, carvings, and similar forms of artistic expression.

It is disheartening to witness the disdain with which we treat these works. A notable example is the burning of artifacts by Bishop Chinasa Nwosu of the Royal Church in the East who gained recognition for setting ablaze ancient sacred objects, branding them as “idols” and “accursed things.” He also opposes the idea of returning the Benin Bronzes and Ife Heads held in museums to Nigeria, arguing that they are not consecrated to God and are therefore deemed idols.

Even more troubling is the fact that some occupiers of key traditional positions (those whose positions are sustained in the democratic structure of Nigeria because of their roles as preservers of traditional customs and beliefs) and are thus supposed to be custodians of these artifacts, are themselves advocating their destruction. In2021, the Oluwo of Iwoland in Osun State, Oba Abdulrasheed Akanbi, urged Yoruba traditional rulers to cease visiting shrines. This should be disconcerting in light of former President Muhammadu Buhari’s handover of returned artifacts to the Oba of Benin, rather than housing them in any of the nation’s museums. Nigeria’s cultural artifacts are now subject to the discretion of persons who may, in the future, advocate their destruction should they adopt a new belief system.

The aforementioned attitude is precisely what made news about Roman Catholic priest, Paul Obayi, all the more extraordinary and unexpected. Reports noted that he collected and safeguarded numerous traditional pre-Christian religious artifacts in the South-East, artifacts that new converts to Christianity had intended to burn. Among his collection are carvings of pagan deities and masks, some of which are over a century old and held deep significance in the pre-Christian beliefs of the Igbo. These objects were considered sacred and believed to possess supernatural powers. Predictably, the priest faced criticism for his actions, with calls for the artifacts, some of which have existed for over 200 years, to be destroyed. This was surprising because churches, inadvertently or otherwise, are known to discourage active participation in traditional rites and festivities, severing the threads that connect us to our cultural tapestry.

The destruction or poor treatment of the ancient works of our ancestors is not isolated from the concurrent erosion of our intangible cultural heritage. As we witness the disregard for physical relics of our past, we also bear witness to the abandonment and fading of our intangible traditions. When Christian communities in Nigeria censure a gospel singer for incorporating Yoruba words rooted in spiritual practices, it echoes the broader sentiment of discarding anything associated with our ancestors’ creations. Sadly, Nigeria’s rich oral traditions, ancestral stories, vibrant music, and spirited dances are being consigned to oblivion.

On the Islamic front, the recent controversy over Isese festival in Ilorin, Kwara State serves as a reminder of this conflict. The emir and a Muslim group banned the festival, arguing against “idolatry.” How can one persuade the citizens of an African nation that it is not unusual for an African to practice an African religion in Africa? Should discussions about religious tolerance be limited to Christianity and Islam alone?

The law has provided little assistance in addressing this challenge. Punishments for destroying artifacts, if ever imposed, are pathetically lenient. Plus, there is a glaring absence of an artifact census or an identification system, which would greatly facilitate the protection of these valuable works. Even the proposed bill aimed at enhancing protection falls short of international standards, and to make matters worse, it has yet to be passed into law since its initiation in 2011. Plus, given this context, it is doubtful whether enforcement officers would diligently carry out their duties.

It is ironic that the West, who taught us long ago to destroy our ancient religious artifacts and edifices on religious grounds, are now more likely to safeguard and preserve these artifacts better than Nigerians would. Nonetheless, Nigeria must also confront the challenges it faces in preserving its cultural heritage at home and decide what is best for the art.

Seun Lari-Williams wrote in via [email protected]