From what the eyes can see, President Bola Tinubu truly deserves commendation and homage because he has already spent about 127 days in office as President and Commander-in-Chief of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. We know from bitter experience that it is no easy task to wear the crown in black Africa’s most populous nation, Nigeria. But of greater significance is the fact that during his four months in office, President Tinubu’s name has become synonymous with the phrase ‘fuel subsidy is gone’, a phrase he used during his acceptance speech and one which, he insists, will usher in a new lease of life in Nigeria. In addition, gone with fuel subsidy are many other things, some gone for our general good, some gone far, far away beyond our reach and some gone not too far away but close enough to give us nightmares. They are so many, we cannot count all: gone is the twilight of former President Muhammadu Buhari’s administration, gone is our self-worth and dignity, gone are the long queues at petrol stations, gone are the prices of fertiliser and food items in the market; transport fare, unemployment, hunger, disease, school fees, ASUU strikes-almost everything is gone with the fuel subsidy.

However, one thing has refused to go away and that is the poor workers in the cities and the peasants and masses in the rural areas. This is the very class of people who legitimised the power of the President through the ballot box. On election day, they were there. They queued up with dried throats under the baking sun to cast their votes. And what about their votes? The general elections ended more than four months ago but they are still being litigated in the courts, they are being discussed in offices and pubs, they are being assessed by the poor even on the farms and at the market places, they are also the major subject of discussion in the social media. But again, most poor Nigerians have preferred to moan discontent or whisper misgivings about the general elections in the sanctuary of their hearts or homes. Others have sought solace in the churches or mosques, in their workplaces or in their drinking places. The poor are looking up to the courts to tell them sincerely and realistically the outcome of the general elections. They are also asking pertinent questions: why is the evidence before their eyes different from that of the tribunals? Why does the judiciary quite often choose to rely on obscure evidence and technicalities that are unfamiliar to the ordinary man to deliver justice? In very simple terms, the poor are saying that lawyers and judges carry so much baggage of unlearned law that has overtaken the rest of society.

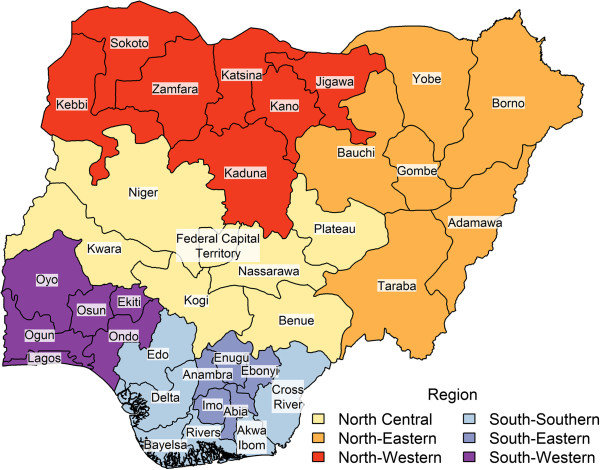

It has been four months now since the decision to throw away fuel subsidy. What about the lives of the poor? Turn everywhere the contours of the lives of the poor are the same. They can hear and speak the language of suffering fluently. Most of them are government workers, but some are fishermen, others are farmers, others are artisans and labourers. From Sokoto to Port Harcourt, they are hungry, they are thirsty and they are in rags. Many of them are homeless or shelter made out of thatch, cardboard, scrap and metal plastic is home to hundreds of Nigerian children and adults. Some are beggars on the streets and from the looks on their faces you will be convinced that they would prefer to be in prison where they can be sure of a bed and three full meals in a day. In the villages, most farmers cannot assess their farmlands for fear of attacks by unknown gunmen. Those who have planted food crops cannot afford fertiliser because it is simply unaffordable. In the cities, the shacks of the poor stand side by side with mansions of tile, stone, glass and concrete owned by Honourable members (senators, members of the House of Reps and the ruling party). This is the only class that owns most property including real estate in Abuja and other capital cities across the country. On the streets, the one thing that can hardly miss the eye, of even the most indifferent spectator, is the remarkable contrast between the sleek, big jeeps and sport utility cars of members of the political class and the line of motor bikes, tricycles, wheelbarrows and hand-pulled carriages all of which are competing for space and right of way on pot-holed roads. But you can be sure that the poor are analysing the system. They are saying that the gap between them and the rich is absolutely intolerable. They are asking questions. They are demanding a better life. They cannot just be thrown away like fuel subsidy.

It is that time of the year when children are expected to return to school for a new session. But what is the state of education in Nigeria and what does the government intend to do with it? Flashback. The period of the first regimes could be conveniently regarded today as the golden age of Nigeria. Leaders like Obafemi Awolowo, Nnamdi Azikiwe, Ahmadu Bello and Tafawa Balewa were able to manage and govern the country with meagre resources derived basically from taxes, cocoa, groundnuts and other agricultural products. The three biggest universities in the country that time namely: University of Ibadan, University of Ife (now Obafemi Awolowo University) and Ahmadu Bello University Zaria ranked among the best universities in the world with expatriates vying for teaching appointments in all faculties. These nationalists were aware that only education could be used for the development and liberation of man. Equally important is the fact that the founding fathers of Nigeria had several things in common: patriotism and the refusal to use the resources of the state for their personal benefit. But beginning from the 1980s up till now, there has been a deliberate plot by the Nigerian ruling elite to destroy public schools and universities. And to do this successfully, public schools in Nigeria are deliberately denied funding by the government. Public school administrators are, therefore, left with no choice than to introduce tuition fees in public primary, secondary and tertiary institutions. The obvious implication of this policy is that the children of the rich and powerful will be educated in expensive private schools and universities at home and abroad while children of the poor will have to accept their lot as hewers of wood and drawers of water.

Nigerian University teachers through their umbrella union, Academic Staff Union of Universities, had over the years had the unpleasant task of drawing government and public attention to the progressive rot in the educational system. The union had also reminded the Nigerian government that it is the social responsibility of any responsible government to fund education because everywhere in the world education is a right and not a privilege. The ASUU struggle has found memorable expression in several appeals to the government, dialogues, warning strikes and sometimes indefinite strikes. But again the judiciary joined the fray, opened its baggage of unlearned law and declared that it was illegal for ASUU to embark on strike. Encouraged essentially by the verdict of the judiciary, the government confiscated the nine months salary of ASUU members. And the children of the poor are asking valid questions: who will pay their tuition fees? Where is their tomorrow?

It is 63 years of independence now and the future of the poor is not rosy. The poor cannot stop asking questions: who knows the price of food items in the markets? Who knows what it means to wake up without a kobo in the pocket? Who knows how to live without a roof in a family of disease and misery? Who knows the agonies of soles without shoes? Who knows how it feels to be a prisoner in a graveyard of freedom? Who knows that the government is killing us without a sword?

Prof. Doki teaches at the University of Jos