Survivors will be interviewed in a series of hearings opening the way for possible compensation, in a bid to settle longstanding grievances and tensions.

“Today is a pivotal moment in our history. This is the day where we demonstrate that as a country, we are capable of resolving our disputes as Zimbabweans, regardless of their complexity or magnitude,” Mnangagwa said in the southern African country’s second-largest city, Bulawayo.

“This initiative is a potent symbol of our collective will to bridge the divides that have separated us for too long,” he added, describing the process as a “pilgrimage towards healing”.

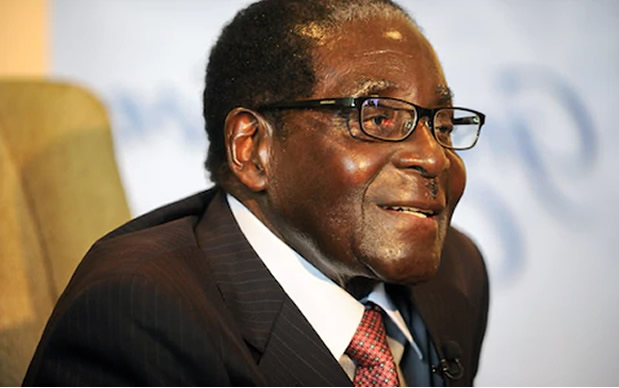

The so-called Gukurahundi massacres took place a few years after Zimbabwe’s independence from Britain, as former leader Robert Mugabe asserted his power.

Starting in 1983, Mugabe deployed an elite North Korean-trained army unit to crack down on a revolt in Bulawayo’s western Matabeleland region, the heartland of the Ndebele minority.

They killed an estimated 20,000 people over several years, according to the Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace in Zimbabwe, a toll supported by Amnesty International.

The operation was named Gukurahundi, a term in the majority Shona language that loosely translates as “the early rain that washes away the chaff”.

Critics say it targeted dissidents loyal to Mugabe’s rival, fellow revolutionary leader Joshua Nkomo. Most of the victims belonged to the minority Ndebele tribe.

– ‘Bad patch’ –

Mugabe, who died in 2019, never acknowledged responsibility for the massacres, dismissing evidence gathered by Amnesty International as a “heap of lies”.

After taking power in 2017, Mnangagwa promised a resolution and set up a panel of chiefs to probe the massacres. The 72 chiefs will now preside over the village hearings.

But activists said the process was flawed and got off on the wrong foot, since there had been no official government apology.

“The launch was a great opportunity to say sorry, but he (Mnangagwa) did not. He should have used that opportunity,” said Buster Magwizi, a spokesman for veterans of ZPRA, a former liberation armed group loyal to Nkomo.

Mnangagwa, who has previously said the massacre was “a bad patch” in Zimbabwe’s history, was security minister at the time but has always denied any responsibility.

“It is unfortunate that the exercise that must bring healing, closure, is micro-managed by those whose hands are dripping of the blood of the innocent people who were killed,” Mbuso Fuzwayo of Ibhetshu LikaZulu, a pressure group, told AFP.

AFP