The problem of lack of access to quality healthcare services is a major challenge in the country despite the country’s National Health Act backing access to healthcare for all Nigerians through the basic minimum package of health services. However, the problem of access to health services is a bigger challenge for persons living with disabilities with many of them facing ill-treatment, neglect, stigma, and discrimination when they go to healthcare facilities to access care. OLUWATOBILOBA JAIYEOLA, in this report, spoke with some persons living with disabilities on the range of barriers they face when accessing healthcare services, particularly in government hospitals.

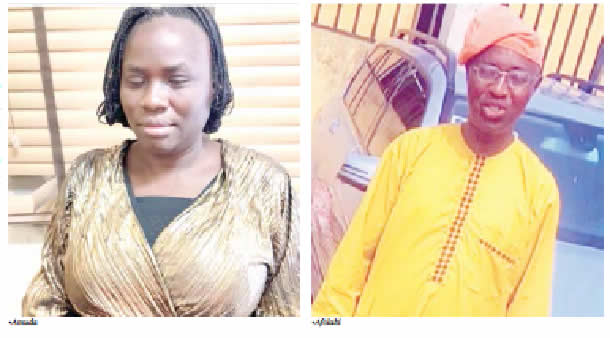

When Ayomide Amuda, in her 40s, rushed into Ikorodu General Hospital, her son was gasping for air. His asthma had kicked in, beyond the control of his inhalers. But her urgency to save him was met by healthcare workers who stood aloof and seemingly less concerned about her quest for prompt attention and treatment.

When they weren’t ignoring her, the nurses were shoving her around. Her son, who also doubles as her guide because she is visually impaired, lies in a corner helplessly. Since she lost her sight, Amuda had relied on other people’s sight in hospitals, at home, in the market, and everywhere.

As soon as her son came of age, he slipped into the role of his mother’s guide. But now, the guide was ill, and no one was willing to help his mother.

She said, “Normally it is my son that assists me when I need to visit the hospital for any reason but at that time, he was sick, and he was the one that needed help and it was tough for us. It was very tough.

“We needed to be going from one place to another doing different things, making payments, doing tests, etc., and without a guide, that means it should be left in the hands of the hospital staff to do for me. Instead, they kept complaining that they don’t have my time.”

There is only so much a mum’s heart can take when her child is in danger, so Amuda cried for help, asking to be taken to the hospital’s welfare unit. The welfare staff on duty didn’t understand their duty and they turned their back on her.

Describing her experience, Amuda stated, “I asked the nurses for direction to the social welfare unit in the hospital, someone took me to the unit and by the time I got there they said they are only two on duty and none of them can leave their post to assist me.

“They blamed me for not coming to the hospital with someone that could help me and refused to leave their post to assist me. I said I thought the social welfare unit was supposed to cater to persons with disabilities and maybe the old, they replied that it wasn’t their duty to follow people like me around and that we should always come along with someone to the hospital, or not come at all if we are not with anyone to help.”

It was when her son soon fainted that the hospital workers remembered their job, she said, noting that it was then that medical personnel swarmed the boy, trying to save his life at the last minute.

They succeeded and admitted her son, but she still needed the help of an outsider.

“That day, my son fainted, that was when they deemed it fit and saw it was an emergency. So, they eventually came and rushed him, but they left me, and I didn’t follow them again. If I had brought my guide, I would have been following them every step of the way to make sure my son was okay.

“I eventually had to call one of my friends, he is also blind but he’s a partially sighted person, so he was the one that came and was assisting me all over the place and they put my son on admission, but he had to leave eventually,” she added.

After her friend left, Amuda had to ask that her six-year-old daughter be brought to her. Neglected by the health workers around her, she said she had to rely on the guidance of a child to help herself and her other child.

According to Amuda, her son could have died because she was blind and the nurses on duty didn’t care. “I felt very bad being treated this way because if my son had died that time because of the way I was treated, I don’t know what I would have done to myself.

“I started blaming myself and feeling bad that if I was not in this condition, I would have been able to be there and be present for my son in his time of need. I would have been able to assist him to do everything. Even my six-year-old daughter later got ill after her brother got discharged.

“All these made me feel very guilty because it was like I exposed her to something she was not supposed to be exposed to and I was very unhappy,” she narrated.

Madam Amuda is not alone in this type of challenge. In 2021, the Minister of Health, Osagie Ehanire, said about 0.78 per cent (1.56 million) Nigerians suffered from blindness during World Sight Day.

Many of these visually impaired persons often face serious challenges when they need medical assistance, even though this is against the ‘Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities (Prohibition) Act, 2018’.

A portion of the Act states that the “Government shall guarantee that persons with disabilities have unfettered access to adequate health care without discrimination on the basis of disability.”

But Kayode Afolabi, another person with visual impairment disagrees that there is a law that guarantees him access to healthcare services in hospitals.

Narrating his experience, he said, “Going to the hospital with my condition is often tough. If I don’t go with anyone, no one would assist me. The time I went alone, I found it very difficult to get help from staff and even patients.

“When nurses notice my condition, some of them act well, some will harshly tell me to go and sit down there ‘we are coming we are coming’. Some have feelings for others though and try to help.

“I was once at LASUTH, though, at the initial stage of my impairment. When I got there, some nurses weren’t helpful and neither were the patients but they also have their own problems that they are dealing with. After then, I stopped going to general hospitals.”

He added, “We face a lot of discrimination in the hospital and even everywhere but we still have few good Nigerians who really understand our plight.”

The visually impaired persons are not alone in facing discrimination from hospitals; it is a common sad tale amongst persons living with disabilities.

People with hearing impairment often complain about their inability to communicate with medical personnel while people in wheelchairs struggle with access to medical facilities because of a lack of ramps and other physical facilities.

Since she was wrongfully injected as a child, Ekiti State indigene, Oluwatobi Olagunju, has had to depend on crushes and a caliper shoe for mobility.

Moving around is a struggle for her, and visiting hospitals only aggravates it, although she said, she occasionally meets angels in human forms. She said it isn’t only hospital staff that reminds her of her condition.

“One time, the woman selling snacks at the General hospital Ikorodu was also looking down on me. The lady was very rude.

“I was the first person to call her and when I did, she ignored me but when other people called, she answered. When she eventually answered she flung the snacks and was like leave me alone and I was confused. I was wondering what I did to her. She started eyeing me up to down like who is she and what is she saying.

“I felt very bad and started crying like what is all this? The matron stood up for me and started talking to her. The matron asked her ‘what has this lady done to you that you are abusing her’. The woman corrected her. She told her that what she did was very wrong because she saw how I felt and saw I was crying,” she narrated.